Writing stories has become part of my engagement with my academic life, it helps me to keep myself creative at the same time that allows me to express feelings and thoughts that otherwise I would struggle to share. The story I present this time was born as part of a storytelling workshop in which I participated. The fiction oganizes my readings on theories of narrative in a way that they were easier to understand.

Hoping that you see the benefits and delights of storytelling, I share this academic fiction with you.

Edgar Rodríguez Sánchez

*

Looking for Jerome

I

[Davie Village. Vancouver. 9780199827237]

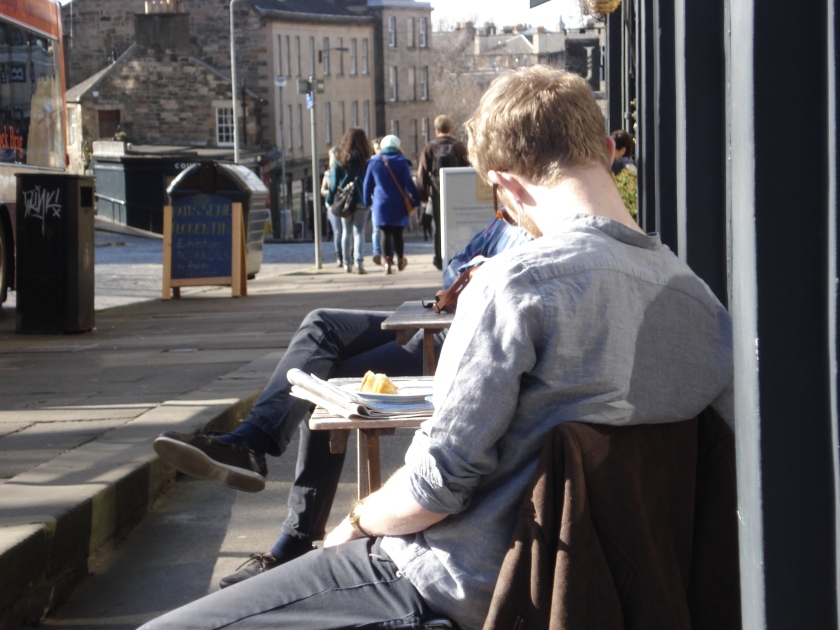

Photo by Edgar Rodríguez

Elliot attacked with all the vigour his pelvis was able to demonstrate. He felt proud of the easy and furtive occasion he had in front of him. On a silver platter he had gotten someone to share his bed with. On the corner of Davie Street and Beach Avenue, just before surrendering to another night of wait for something powerful enough to take him out of his quotidian existence, he did the ritual that uncountable times used to do in an unsuccessful way. Full body scan and then stopping for a deep gaze in the eyes, searching for an encounter with those green spirits of eyes to mirror his existence, turning his head to simulate discretion when in fact it was intention. Six steps further, distance enough to verify if the ritual had worked, if he had succeeded in this courtship dance or if once again he had been dancing solo for an inexistent audience. When Elliot turned his head, he realized the dance had been successful; the verification of the mutual interest had worked and his counterpart was already looking at him. A few phrases to measure the level of desire. Further questions to calculate the potential risk. Less than six trips of the seconds hand of the clock and Elliot attacked with all the vigour his pelvis was able to demonstrate. Those superlative buttocks surrendered to his power.

However, according to what Elliot expected from that encounter, something was falling short of standards. The voice. There was no vocal response accompanying the pendular ins and outs of his member. Changes of rhythm, speed, strenght, position, angle… everything he tried was unsuccessful to obtain the effect he wanted. Silence was attached to that unaffected body. Elliot was connected to a self-immersed person, to a person with absent emotions. A flat with panoramic nocturnal view, a guy with alluring physique; both the guy and the flat were desired with impeccable precision. It could have been the perfect scene but all he had at the end was a mediocre orgasm.

The following morning to which he called a miserable episode, Elliot found getting up for the institute very difficult. He was about to stay in bed, he felt that even the life of a man with brain death was more meaningful than his. That feeling of misery was what made him get up, go to his touchscreen, and predict the activities for his day. This time he did not mention that he would feel energized and optimistic. In other occasions when he wrote something similar, his uncontrollable dynamism and gratuitous smiles left him exhausted and alienated. He only wrote in the touchscreen a spontaneous appearance at the school; that was the safest, most direct, and simplest thing to do. No emotions attached, those were already complicated enough, so adding them to daily life activities was pointless. Thus he appeared in the institute for narrative technologies. That was the highest level he could reach in the construction of lives: a technologic institute. While in front of his screen he rearranged paragraphs and polished phrases. On the side he analyzed in a little notebook what had gone wrong the last night. Notwithstanding it should have been an exciting encounter full of adrenaline, the tailored episode left a corrosive dissatisfaction in him.

The instructor worked with a student in what seemed to be a female dragon illustrated in 3D. The visual project attracted Elliot’s attention for a few seconds. Velveted wings and a multicoloured chestplate; seeing the creature flying over a deserted land was an entertaining spectacle. However, Elliot moved his head in disapproval, “a beginner”, he thought. He already knew the implications of working with visual contents. “That dragon will last a minute at most”, he said to himself. Once the dragon landed, she started to cough convulsively, rainbow phlegms came out of her mouth. The cough became vomit and an iridescent jet came out through her throat. The jet was so beautiful that it contrasted with the idea that it was her insides which were propelled from her body. The brilliance was so intense that one could get their eyes sore if looking the colours directly. The spectacle attracted the attention of the students and they got closer to see what happened. Rivers of a coloured viscous fluid inundated the wasteland. There was no space for the mythic reptile. When the level of the liquid reached her face, the violently expelled liquid started to get into her again through the orifices of nose, mouth, and ears. The dragon showed signs of asphyxia, her eyes popped out from their sockets. Her eyelids were wide open, so much that for several seconds one could see terror in them. When there was no more air to breed and the death rattles defeated her, a static inert body could be seen sinking in the tridimensional inks.

“Her creator pretended to make her immortal, and all you can witness here is death. This is a phrase you can use in one of your stories”. The instructor said while cleaning digitally the mess of colourful vomit. “Newbies still believe in the archaic saying that an image is worth a thousand words. In their first adventures they focus their efforts on creating images thinking they will be able to explain complex concepts with simple images. Not mattering literature has warned of the underlying difficulties in the interpretation of visual narratives. How to create an immortal being only with images?

This is a question for everyone, not only for your inexpert classmate. We can draw dragons, landscapes, geometric shapes, fruit baskets still life and fresh, we can draw rainbowed vomit. However, how can we draw immortality? So I suggest if you are in this class, focus on reviewing the corresponding contents. Work with images in the courses in which you have the support for that. Professors Eisner or Tufte can tell you more in that regard. They argue everything can be represented through visual stimulus. I can show my skepticism about it but of course I am not an expert. For now just focus on the structure, that is the area in which I am going to tutor you. How do you aim to create mythic or fantastic beings if you don’t have a strong structure to support your story? I don’t want to imagine you experimenting with Magic Geographies in your Romance Languages course, or making cultural critiques in your Psychology of the Characters course. Whatever you want to make of your life, it needs to be done now; the only thing that can save you from a woeful life is the skill to write your own life story. But you’re not going to have a positive outcome if you draw three dimensional dragons when you’re supposed to outline your story.”

The instructor approached Elliot to see his monitor, he read the first lines of the table of contents. “Traditional structures, self-descriptive chapters, chronological sequences, psychic time which doesn’t saturate the chronological time, and a third-person narrative voice. I like your organization, Elliot.” The instructor saw with surprise the alternative scheme Elliot had outlined in his booklet. “So, you’re flirting with the old school… not many students are using paper and pen anymore”

“There’s something I’m doing wrong.”

“In which regard?”

“With my characters, or with the emotional atmosphere, or with the tone of the narrative, or… actually I don’t know what’s happening.”

“I don’t think your problem is structural.”

“Tell me what’s my problem then because, frankly, I don’t understand it. I have written myself in the most enjoyable scenarios, with characters who satisfy every single one of my whims and fancies, in circumstances in which one could experience not only euphoria but also a more consistent joy. Yesterday, for instance, I released the story I had been working on during the last two months. The geography was identical to the city, the weather was ideally described to the extent that Vancouver has never seen a sunset like that. Everything in my story was so rich; full of details both in the environment and in the character. I was written as my alter ego but in the crucial moment of the story, my co-protagonist didn’t correspond to my emotions. He was immersed in a hopeless stoicism.”

“We’ve talked about this already and no, your problem is not, definitely, about structure. I must admit that at this point in time my capacities to help you have been overpassed. I don’t know what is the problem of your characters. I don’t know what is the origin… I’m only an instructor… Look for Professor Bruner. You’ve been one of the most advanced students but I don’t think that the members of the staff can help you, not even the ones who are already professors. This is only a technologic institute; its author thought the concept very well so here we teach applied writing. Appliances to help people to write appealing lives, to create credible ambiences, to write arguments which lay on the classical types of stories and, at its best, to construct characters with one, two, and perhaps three personality characteristics, but no more. This institute doesn’t deal with situations as complex as the ones you’re experiencing. Look for professor Bruner. If someone can help you, it must be him.”

II

[New York University, School of Law. 067401099X]

There must have been years ago when Jerome Bruner should have died, but rumors say he had not found the courage or the way to write his own death. Bruner was one of the pioneers of the narrative turn; in the second half of the 20th century he and other authors proposed that life was not real, they said life was not a group of sequenced happenings. They proposed life was meaningless, that life seemed to be meaningful because we wanted to believe so. They suggested that daily happenings occurring in our lives, the ones that we believed as the foundations of our current situation, were a connection only justified by our necessity to find coherence in our lives. Frederick Mayer, another contributor to the narrative development, wrote a book entitled “the storytelling animal” in which he discussed the role of stories in politics. He described how research in evolution had shown humans had developed the ability to tell stories as a method for survival. The skill to tell stories is what made the difference between the proto-humans and the modern humans. Stories can influence our actions, emotions, and thoughts. It is through stories that we create an illusion of having options.

When research in genetics was at its peak, when humankind believed everything could be created and anticipated by the DNA, scientists became arrogant. But there was a group of rebels who did not accept that everything was controlled by genes. Studies with identical twins were pivotal in the development of what we understand now about life. When scientists realized that identical twins developed different characteristics of personality and behaviour when separated at birth, geneticists began to credit the impact of the environment. Studies continued and acknowledged that two people with the same predisposition to a medical condition got different results; they realized that epigenetic factors had been underestimated in previous studies. But what made scientist like Bruner and Mayer special was that other scholars belittled stories, the narrations people made. They did not appreciated the role that stories play in culture, the same role that genes play in evolution.

As Elliot had spent his life in the institute learning how to write, he missed the ‘know why’ aspect of writing and that was what he wanted to find out. He decided then to travel to New York in the ancient way; he took a flight instead of writing his appearance via his touchscreen. On his way he read as much as he could about the history of narrative theory and the philosophy behind the social constructionism. Reading about the ontology of what he had been doing at a purely technical level was an enlightenment, it made more meaningful the talk he was to attend.

Getting a ticket to listen to Professor Bruner was a hit of luck; New York University’s Skirball Center for the Performing Arts was overcrowded. Elliot found his seat in the fourth row among undergraduates, he noticed how impressively young they looked but he assumed they were not as young as they represented because the event was targeted to postgraduate students and mature scholars. The auditorium seemed more appropriate for a performance than for an academic talk. “It’s because of the scale of the event, it needs to be a venue like this for such a big number of people”, he thought while looking at the second floor which was also fully packed. When Professor Bruner entered the stage, the silence entered with him and all the voices in the audience faded. His presence was a mixture of vulnerability and power while seeing him talking. Age and wisdom were the elements interplaying to form this contrast.

“We are biological beings and biology is affected by genes. But we are also cultural beings and culture is affected by the stories we tell. Perhaps a child survives because their immune system is strong thanks to their genes, but that organism also survives because her parents tell her how to protect herself from dangers and at that point stories play a transcendental part. Stories help us to create and disseminate culture, they give meaning, give us identity, and let us find coherence where in reality there is only randomness. In other words, if I am living a miserable life, it is not that my life has been a series of miserable events but it is me who has interpreted random events as consequential misery. I have connected those happenings, transformed them into a story, with a dramatic hint assigned by me, in which I have portrayed myself as a victim and in summary, I have lived a plot of a character with a run-down life. That summary is absolutely subjective, the end and moral is imposed by me to the story I decided to tell myself. Along those lines, Pierre Bourdieu detailed the concept of linguistic capital, he explained that knowledge and proficiency of spoken and written language allow access to power structures and it is possible to transform it into economic goods. Capitalist societies took advantage of their knowledge of the human beings as storytellers to develop a technology in which they could write in advance a tailored story for users to tell and love accordingly.”

Elliot found the courage to raise his hand in the middle of the audience to interrupt Professor Bruner’s speech and ask him a question. Notwithstanding it is a common practice that speakers invite the audience to feel free to interrupt their speech, make comments or questions, and thus make the talk more interactive, it is also a common practice that the audience does not interrupt and remain silent until the end of the talk. In a master class like that, with a thousand of people inside the room, it was a brave act, yet inappropriate. Elliot raised his hand to intervene nevertheless.

“Yes, profesor Bruner, everything you’re saying I already know it. I’ve read enough about that but what I…”

Professor Bruner interrupted the motion without a hint of surprise. Elliot however was shocked when the old man addressed him by his name in the most familiar way. “Elliot, you have come here looking for a transcendental truth you want me to reveal. When I was informed you would be attending, I experienced the thrill of waiting for the event of the century. I was longing to listen to what you had to say as if I were about to listen to a postmodern Oscar Wilde. Your opening lines are rather disappointing; that arrogance in believing you know it all. If you have read enough already, then what are you doing here?”

Neither Elliot nor anyone in the audience seemed to know why Professor Bruner knew him well. Silenced by the impossibly severe but impassive response the speaker had given to Elliot, everyone held their breath for a few seconds before Professor Bruner resumed his talk.

“Editorials were the most interested in those happenings, but they were not the most powerful to access that knowledge. Andersen & McDonough however, bought the rights to develop tools and concepts to guarantee the development of narrative technologies. And they were successful, it seemed a promising future, a future full of possibilities to experiment the power of words. What happened next was that the first narration written with Andersen & McDonough technologies, in which readers observed the happenings exactly in the way they had been written, boosted the proliferation of mass-produced heroic characters and utopian worlds. At that time I used to work as a development consultant and I warned them about the unsustainable conditions they were creating; entire worlds with no justification, heroes without a background to support their heroic actions. Characters which were born by spontaneous generation, they had no follow-up; appearances in first scenes and total abandonment in the second chapter in a species of literary limbo that impeded them to see the light again. That was the common pattern. Their literary worlds were imperfect because authors did not reflect the circumstances that characters would experience in the geographical world. They used to write, encouraged by A&M, the stories of the psychic worlds where they wanted to live.”

For the surprise of the audience, Elliot interrupted again in a frantic way. “But how was that a problem?”

“Tell me, Elliot, have you ever experienced a world where everything is absolutely perfect?”

“No. Never.”

“How could you develop a fiction in which everything is perfection? Imagination, even if it seems unlimited, it’s condemned in a social frame which restricts. Imagination allows freedom to some extent but it’s not a freedom coming from nowhere and going to infinity. Authors’ imagination only could origin worlds similar to the ones they’ve had contact with”.

In an almost inaudible tone Elliot said to himself, “that sounds familiar.”

“It’s not surprising. Several authors have concluded the same. Foucault?”

“No, Kushner. In Angels in America. Harper tells Prior that imagination is just a way to mix pieces of our lives in a way which seems original; even our hallucinations and dreams in which we’re apparently taken by a free flow of ideas, those dreams are dominated by a referential frame supported by what we’ve already lived.”

“That was exactly what happened to authors who pioneered in the interactive narrative developed by A&M, they aimed to write perfect worlds which promised to solve the issues of Humanity and of their own humanity. The generation of the millenium; their literary worlds were fallible, they had fractures, hundreds of gaps and therefore secondary and incidental characters lived infamous lives. Other authors entered into psychotic processes when looking for an utopia which they were not even able to write without failures. The worst thing happened when McDonough died, Andersen played with fire. He wrote a text addressing McDonough’s life with the purpose of claiming him to Death. Entire chapters describing the psychology of the character, thoroughly hand sewing the pieces that connected the events in McDonough’s life as they were believed to happen. The text continuously described his physical characteristics so the literary one was identical to the mortal one. Same family background, same school, same life triggers.”

“In other words, he wrote a biography.”

“Yes and no. Andersen knew if he wanted to see the same McDonough, he must describe everything exactly as it had happened. And here I take the license to say “exactly” because I’ve made clear there’s no such a thing as an accurate description of the happenings as they occur, all we can have is a storied interpretation. Andersen knew he couldn’t reproduce the events. And something even worse, he didn’t want it either. Because that implied that he would lose McDonough in the same way he had already experienced the loss. Thus with a slight change in the day of McDonough’s death Andersen assured that wouldn’t happen again.”

When the book was ready, McDonough came back to the life he had been assigned as in a Mary Shelley’s book. McDonough came back almost identical, almost. He looked slightly more intelligent, slightly more beautiful, slightly more educated. All those aspects showed he had been written with the admiration he had been object. He also seemed slightly less complex, all that because he was just… a character. After his no-death, McDonough became one of the most prolific writers. With the gift of immortality, a gift he wasn’t conscious of, he advocated his life to fill the gaps in books by the millennial authors; those who seemed to spread stories with abandoned incidental characters. Millions of characters whose lives consisted in a one-off appearance only to give an important message to the leading character, to be part of a crowd attending a party but whose connection with the host is unknown, to be beachgoers to make credible that the protagonists are spending summer in Gran Canaria. McDonough considered he was acting for good when writing stories which made brighter the lives of characters which consisted in repeating an action again and again. McDonough, who had been written with ethical principles slightly higher than the ones he died with, realized the privilege of knowing that we are the ones who give meaning to life. So he created the institutions of education in narrative.

At that moment, inequality was even greater than when money was the capital. People who were not proficient at writing were condemned to live in a simple universe, with simple characters, and simple plots. Illiterate people were condemned to live lives written by the whims of others. If their authors were benevolent they would write that their main characters were “happy”. For people with problems in grammar, syntax, and spelling, their lives meant whole chapters of terrible confusion, so much that at the first day of their lives they already wanted to kill themselves.

Being skilled at writing became the new currency with the highest pay rate, meanwhile the illiterates were the new poor. Being bad at writing was a synonym of a tough life, which reverted the trend during the postmodern era when being proficient at words was no guarantee of anything. With this new capital, people lived the lives they were able to write for themselves. People born in that era came to the world because a random author decided to write about them, those characters had a borrowed consciousness (their author’s consciousness) and if they wanted their own life they should have to mature so they could think and write independently. Only that could guarantee self-awareness beyond what their author had given to them in their book. Should not they succeed, their only possible destiny would be to live in a few lines in the someone else’s story.”

Elliot was abstracted for several minutes. He had listened to Jerome but he could not give credit to what he was listening. He closed his eyes arrested by his heart beating at an unusual pace. He knew what a Proustian moment was but he was not sure he had experienced one, not until Bruner’s words echoed into his head. When he opened his eyes, he continued with what seemed a one-to-one talk and not a master class for a large audience. “What do you mean with ‘people born in this era are born from someone else’s story?’”

“Well, people realized that narrative technologies allowed them to design the life they wanted, not only making small changes in their current ones. Thus they included modifications in the partners they would have, the place where they were to live, the body they were to face the world with. People know they’re creating incomplete worlds, unrealistic worlds; characters lacking complexity, but they have got used to unfinished geographies, sequences with sudden jumps because they don’t know how to write a transition; they have got used to characters who respond with almost human reactions. They have got used. Some of them have even forgotten they’re living a plot they wrote in a time which they don’t have memory of. Those who remember the charade they are living in, depending on their mental sharpness, try to edit their narration and close it with dignity. Some dare to write their own death, but when they know it’s about to happen, they write a prequel or an alternative ending. All that with the only purpose of continuing with the illusion narrative gave them: the false certainty of knowing what life is.”

“But… what’s the difference between people who were born from someone else’s narrative and those who are born in the ‘natural’ way?”

“Do you mean knowing someone, fall in the turmoil of love, etcetera, until forming a family? I haven’t seen a single couple relating in the ‘natural’ way as you say. What I see is individuals relating with themselves, learning to write in the best possible way to get detached from their authors’ consciousness and then write their lives in their own terms. Life conceived in that way includes writing the partner they’ve always dreamed of, designing it in the way they think it will make them happy. People nowadays do not see the point of relating with people who already exist, because they’re unpredictable, that doesn’t guarantee them the knowledge of their future. So they prefer to write a life with characters who give them sureness.”

By then Elliot had come to the point of facing a thought he hadn’t dared to speak out loud.

“I know what’s in your mind, Elliot. I know it. And I think you’re about to cross a boundary, you’re about to gain your consciousness. You’re wondering why you don’t think often of your parents even if you see them everyday in that picture over the fireplace in your flat. You’re wondering why owning a flat in Beach Avenue and Davie Street seems so normal to you even though it would be practically impossible for a student to afford, you’re now suspicious about the panoramic view to the yacht club, and the fact that it is always a nocturnal view. You’re wondering where are the relationships with your friends, you know you have them, you know the exact number of the friends you have, you see the figure everyday, as if you had a screen with a reminder of all of them, but you can’t mention who they’re and you haven’t seen them outside your screen. You wonder why you don’t know your instructor’s name even if you seem to get along very well with him. You wonder why the student of the rainbow dragon doesn’t have a name. You wonder why in spite of being a committed student you’re unable to write a different scene to the one you’ve written about the furtive encounter, you seem a brilliant student but your narrative seems constrained in a frame which doesn’t allow you to create a different world.

At this point you have elucidated you’re a character, Elliot. You’re living in the story of someone else. You’ve lived this story since its author visited Vancouver and a deep love for the city emerged. This love draws also on a spontaneous encounter that happened there. You’re that encounter in Davie Street. There’s no more information about you beyond that scene. Your instructor and me are very surprised by the fact that an incidental character is developing this level of consciousness. We’ve analyzed the book and concluded that you’re a group of paragraphs in a well-cared structure; the episode in which you appear describes without limiting the readers’ opportunities to interpret. The author was a wordsmith, he took care of the readers and therefore of the characters, you included. It’s a hit of luck that you bumped into someone who wrote about you in a passage which is short in words but extensive in meaning. It seems you left a deep impression in him. By now you’ve already died in the chronological time but you still have an opportunity in the psychic time.

You’re an incidental character, Elliot, you’re a fortuity. A chance which triggered a number of happenings in the life of your author, but you only live in the page ten. Apparently there was a real Elliot living in that address in 2008, which means you’re the product of a recollection and not just a fantasy, that gives you more hope. A few lines and that’s it, I don’t know more about you. You can find the book at the fifth floor of the university library in the corridor of the HQ’s.”

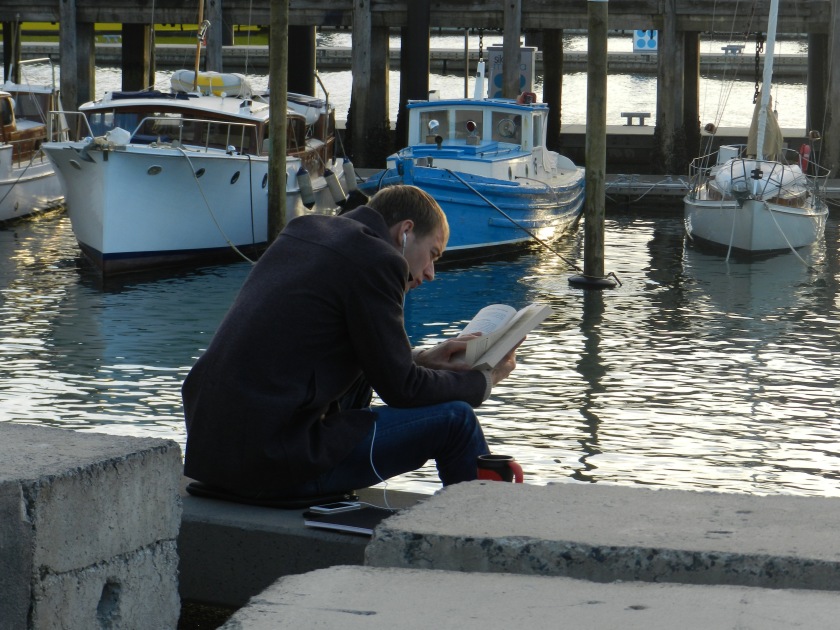

Photo by Edgar Rodríguez

*